|

From a pure entertainment perspective, fans love the NBA Draft. It's a suspenseful evening of making bets on the futures of individuals, where no person in the world can accurately predict or know how these multi-million dollar investments will work out. Some picks resemble hope, others frustration and lack of clarity... but all are done with a plan in mind. Draft night is that unique evening where all thirty teams are, in some form, directly in competition with each other. From an organizational perspective, the draft is the culmination of one of the largest areas for research, data collection and group decision-making areas in the league. Each team's front office spends countless hours analyzing, gathering and debating these prospects all in the name of moving the franchise in the right direction. Seeing the efforts compiled by scouts and the like places even more value on those players once they are selected. It's not quite that simplistic though, where each team waits their turn and picks their best selection available, then waits for their next turn in line. The NBA allows teams to trade their draft picks and selections when both teams deem it's advantageous to swap positions. It helps sweeten the pot for mid-season deals between contenders and struggling teams, among other reasons, and has become an integral part of the trade landscape. Pick trading and swapping is so prevalent that several teams have based their entire building strategy upon hoarding them, evaluating the best players they can get with them, and figuring out the rest later. As of the end of May, 14 of the 30 first-round picks and 35 picks overall have already switched hands -- a whopping 58 percent of all draft picks. Those are all the results of trades made at earlier dates, long before the draft order and the season itself is decided. To further add to the chaos, teams can begin making trades and deals again prior to the draft or on draft night itself. The last few seasons the draft has become an environment of pandemonium due to unforeseen draft day trades. Here are the number of draft picks that changed hands on draft night over the past five seasons:

2012 appears as more of an aberration than indication of an upward trend starting in 2013, but the point is that the amount of draft picks that change hands fluctuates highly every year. Trying to anticipate how many trades will happen might be futile due to the insane number of variables at play. At the very least we can try to identify the types of situations that cause teams to engage in draft-day trades most frequently.

The Cap-Clearing Contender Scenario In a cap-clearing scenario, one team will trade a player under contract with the goal of getting their contract off the books being paramount. The typical profile of a team looking to clear cap space is that of a contender who assembled an expensive roster to win-now and must deal with the long-term consequences. Their best option is to pair draft picks with a decently large salary in hopes that a team with cap space will take on the contract. The team trading the pick and the salary away likely takes on some minor player, a conditional draft pick and gets the ever-important trade exception created by the disparity of salaries. What they need to do with that cap space is not always the same. Some simply need immediate relief from their heavy payroll. Others want to make minor moves that don't disrupt the core but position them to make a free agency splash that puts them over the hump. As with any trade, it takes two to tango. Finding the right trade partner for these teams requires a massive understanding of the positions all other 29 franchises are in. Trade partners best in this deal are ones that have the financial flexibility to take on some salary if it nets them an extra draft pick. Cleveland did this in their Brendan Haywood acquisition, giving up Alonzo Gee for Haywood and a draft pick (Dwight Powell). Haywood ended up being the more valuable of the two pieces, with a unique $10 million unguaranteed contract that kicked in a year after the trade. Haywood's contract helped the Cavaliers ultimate construct a roster around LeBron, with his trade exception resulting in Timofey Mozgov's mid-season acquisition. That was only possible because the front office had the foresight in 2014 to use their cap space now to provide flexibility later. Based on the length of the contract being discussed in the trade, the effectiveness of that player and the other salaries or contracts to make the trade work, different types of compensation will head one way or another. That said, the most common type of player that's easiest to move is one with a unique contract: unguaranteed contracts. Teams looking to clear cap space will look to acquire one of these, often times giving up a draft pick to do so. Examples: Cavs grab Haywood's unique contract, Bulls send Hinrich to Wizards. 2017 Teams fitting the bill: Portland, Oklahoma City, Toronto The Veteran on the Rebuilding Team The second scenario on this list also features a team looking to clear cap space, though for different reasons. Immediate cap relief, compounded with the addition of a draft pick, is seen as the catalyst for an important turnaround. Teams that are either mired in mediocrity or looking to rebuild completely will entertain this option around the draft. Often those are the teams searching for the ability to hoard draft picks in hopes of a slower retooling of the roster. Most importantly for teams in this scenario is that long-term relief: cap space. Teams that exercise this deal usually have a plan with what they'd do with the cap space, whether it is retaining a marquee restricted free agent due a massive raise or building long-term cap space as they look to contend down the line. Often teams will make a trade one year with the plan of using cap space a year later. Trade partners are vital for this type of scenario to work. The better the player, the more valuable the draft pick must be in return. Any trade partner must not only like the veteran involved in a deal, but be willing to give up a draft pick in order to get them. Examples: Aaron Afflalo-Evan Fournier trade, Thad Young to the Pacers. 2017 Teams fitting the bill: Sacramento, Indiana, Brooklyn, Phoenix The "Trade Up" The premise for the next two types of trade scenarios is simple, albeit hard to predict. Teams fall in love with players during draft season, saying they need to move up in the draft to make sure they get the player and not risk seeing a competitor snatch them up. An aggressive move for a prospect, ramifications of a trade like this can be vast. The better the player/ higher the draft position needed to select them, the more it will cost to move up. Compensation could bleed into future years with other draft picks. Only one common ingredient appears for identifying teams that might be in the trade up category -- multiple first-round picks. Teams that have two or more picks in the first-round have an increased tendency to bundle them together and move up for one player. Regarding trade partners: it doesn't have to be teams that are simply in the beneath "trade down" category or that are looking for an impact player immediately. Sometimes there's a swap to be made of a first-rounder and a guy worth a second-rounder in exchange for a second-round pick and a guy worth a first-rounder. That technically qualifies as trading up or down, but is done with the intent of synching the talent-level with the organizational timeline for success. Part of what makes the draft such a pressure-packed situation is that one unforeseen domino that falls can create the need for quick judgment -- if one player starts to fall, a trade-up can net a quick move on draft night. Examples: 2014 Heat grab Napier, 2015 Nets use Plumlee to get in the first round, 2013 Celtics for Kelly Olynyk. 2017 Teams fitting the bill: Teams with multiple picks (Portland, Brooklyn, Atlanta, Philadelphia, Orlando, Utah) The "Trade Down" There's an obvious relationship between trading up and trading down in many regards, as the currency obviously used to negotiate trading down means your trade partner has a draft pick to offer in return. But trading down is a difficult decision to make, one usually done to maximize value or add multiple pieces. The logic behind "we don't like anybody at this pick, so let's trade down" is sound but rarely how situations play out. Times where a run of talented players all at the same position might occur in a draft, a trade down scenario would be more plausible if a team doesn't have a need there. Or, like in the case of the 2014 Nuggets, the way the draft had turned out thus far presented them with an opportunity to get two players they were considering with the same pick. Planning a trade-down in advance requires feelers with other first-round teams before the draft, knowing who to call if the situation arises that they'd want to trade down. At the end of the day value maximization is the name of the game. Teams only have a few minutes when they're officially "on the clock", so feeling out of the trade-down market takes place beforehand. Pulling the trigger on draft night, regardless of circumstances, requires the right scenario coming to fruition and a quick evaluation of a landscape with constantly moving targets -- after all, there's no knowing exactly what players will be available later in the draft. Examples: 2014 Nuggets with Nurkic and Harris, 2015 Cavaliers with Tyus Jones, 2013 Timberwolves with Trey Burke and Utah. 2017 Teams fitting the bill: Detroit, Charlotte, Oklahoma City, Indiana The "Now For Later" There certainly is such a thing as too many draft picks in one year. Each team finds themselves in different scenarios with how many roster spots they plan to have available next season, and they are forced to budget those openings between the draft and free agency. If a franchise has more draft picks than potential roster spots, they have two main options: draft an international draft-and-stash prospect or trade it for a pick in a later year (or for cash, if the pick is low enough). For pick hoarders who grab future second-round picks, those picks will come due eventually. In the years where they all do, they can pick a slew of international guys, or they can trade one or two and move them down the line to a future year. Further complicating matters are the previously-drafted international prospects that might finally be ready to come to the NBA. Front offices must factor them into the planning for roster spots, so if they would rather have that than a second-rounder, it would make sense to trade a pick now for a pick later. Most common with second-round picks, I'd surmise that this is the most common cause of draft night trades. I am also curious to see how the reformatted two-way D-League contracts effect this system. As an estimate, it would make sense to see fewer of these "now for later" trades if a team can hang onto the pick and retain exclusive rights of a domestic player without having them effect the roster spots or cap scenario too greatly. Examples: Cavs send Allen Crabbe to Portland, Deyonta Davis to the Grizzlies for a future first, Knicks pick up Willy Hernangomez. 2017 Teams fitting the bill: Boston, Philadelphia, Denver, Phoenix, Portland

0 Comments

As the NBA Playoffs have proven, the Cleveland Cavaliers' offensive firepower might be too much for the rest of the league to handle. As I noted in a more detailed post on BBALLBREAKDOWN, Cleveland's entire organization decided to go "all in" on offense, building a roster designed to attack any defense and any type of team, all centered around LeBron James and the pick-and-roll.

So far, that strategy has paid off big for the Cavaliers, winning twelve of thirteen this postseason while having the most efficient offense this postseason by several measures. With LeBron James and Kyrie Irving as two of the most talented ball screen creators in the league, coach Tyronn Lue simplifies the game and lets those two pick apart defenses. As shooters surround the action, there's little opponents can do once the Cavs get any sort of dribble penetration. As a side note, the NBA Finals will be fascinating because the best scheme for preventing dribble penetration off ball screens is to switch, and no team is better at executing a switch than the Golden State Warriors. Cleveland will be armed with counters and quick-hitters to knock the Warriors back, but the push-pull between the teams in their third-straight NBA Finals will be a chess match for the ages. In the video above, I break down three different ways the Cavaliers use the ball screen:

At the end of each section, the video shows how the Cavaliers use the effectiveness of the pick-and-roll and the supreme shooting prowess of Kyle Korver to leverage each other. The pick-and-roll sucks shooters away from Korver, and when defenses pay too much attention to the ball screen, a lethal three point threat becomes open. The inverse is also true, where too much worry about Korver (elite shooters have a "gravity" or gravitational force that sucks defenders towards them) can leave the lane open. Watching ball screen after ball screen isn't the most aesthetically-pleasing style to many basketball purists and casual fans alike. When the pieces work, and with the sheer brilliance of LeBron James, it's hard to argue with its frequent use in Cleveland. Lue has done a great job not over-saturating the playbook with ball screens or dialing them up too frequently during the regular season -- that and that alone is why worry of the Cavs' regular season results was so misguided. The lion's share of preparation from an assistant coach comes in practice and before game day. A good assistant coach prepares his players for the opponent and their personnel as well as preparing their coach for tactical decisions. A good coach, whether head coach or assistant, is a coach who does not need to teach anything to his team on game day.

Head Coaches all differ on what their assistants should be doing on the bench during a game. Some like to be standing the entire game, rarely talking to their assistants unless it is a timeout. Others sit on the front of the bench listening to their top assistant; others flank themselves with an assistant on each side so they are constantly surrounded by ideas. Even receiving ideas can vary from coach to coach. Some want only to ask you questions about what to do, bouncing their ideas off you for approval. Others want you as the assistant to give tons of suggestions (whether you would support implementing them or not) so they can decide what to do with a variety of ideas. As an assistant, you must get a read for your head coach and how to deal with him that best suits the program and his coaching style. But assistants need to do more than simply take in the game, watch and take or make suggestions to the coach. There are a few things that every assistant should do or have with them during a game:

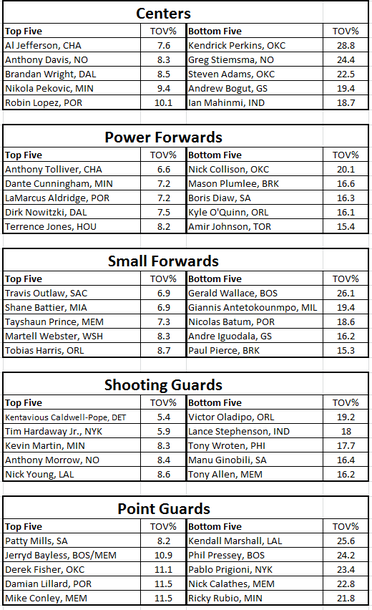

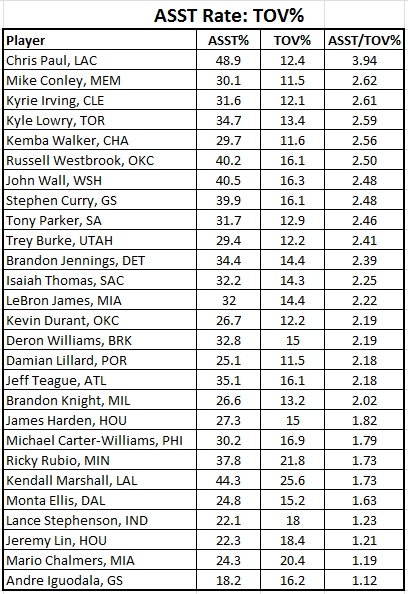

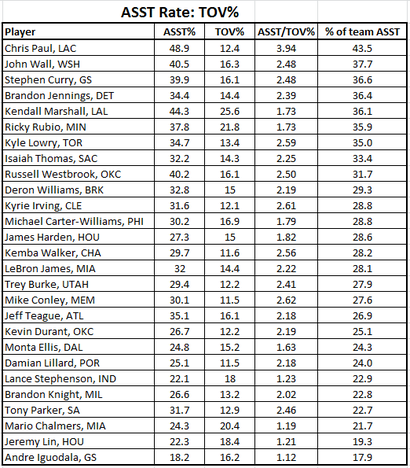

Each assistant should have a separate role on game day, watching for different aspects of the game and being in charge of scheming them. Most high school and even college teams are limited in how many bodies they can have on the bench. Piling too much on your only assistant during a game has a negative effect, both on the preparedness of the players and the flow of ideas between coaches. Here's the way I would prioritize information by assistant: 1. Foul Chart and Timeout Planner The lead assistant is your most trusted confidant and who will help you make the best decisions throughout the game. You should trust that they have a similar feel for the game as you do; as the head coach you don't need charting or writing things town in order to remember what is taking place in the game. The essential information is found in foul chart and timeout planner. Have a list of each player on both teams and keep track of how many fouls they have. Also keep track of both team's timeouts, and during timeouts when the head coach is speaking to the team, check in with the official scorer to make sure your information is accurate. 2. Offensive Charting This may just be my bias as an offensive-minded coach coming through, but I believe seeing what plays work and do not work are vital to the flow of the game. There are only so many defenses you can call in a game; an offensive playbook is usually deeper than a defensive one. Since an opponent will usually change their defense less frequently as well, you should know what plays are effective and which ones they are taking away. In a separate article I will give an example of what I believe to be an effective chart to have on the bench. Whether it is an offensive shot chart, a list of plays your team runs or simply a breakdown of who is scoring or assisting on your baskets, this information will help you effectively call the right plays down the stretch. 3. Hustle Charting The stats that aren't there in stat sheet and won't be kept by the official scorer. As a coaching staff you should strive to reward players who do the little things that help your team but often go unnoticed. Deflecting passes, diving on the floor, taking a charge, those plays matter tremendously. But so does taking note of when a player is not doing the little things: getting backdoored, not blocking out successfully. This gives you tangible evidence as to who is putting forth acceptable effort and who is willing to gain you and your team extra possessions. Again, I will give an example of what I believe to be an effective method for charting hustle in a separate post. A team with more than three assistants can get creative with what the rest of the staff does. Shot charting individual players, charting individual defensive possessions, doing +/- stats for lineup analysis, many more possibilities. Most high school and even some college programs only have three or fewer assistants on the bench at a time. There's no shortage of information to be had; gather as much as you can without overwhelming one individual assistant. They need to watch the flow of the game, not have their head in a pad of paper and a clipboard the entire game. The little things matter in basketball, and the NBA is no exception to that rule despite common conception. It's still a league where attention to detail and doing the "little things" create the razor thin margin for error most teams operate within. In a league where most teams have talent that can score the ball, the teams that win the most games and have the best offenses maximize their possessions, and the efficiency of offenses these days is a large focus of that maximization. That can mean a lot of things: getting shots from the right players or places on the floor, winning offensive rebounding battle, having great sets in special situations (end of clock, baseline and sideline out of bounds), or winning the turnover battle. Turnovers need to be quantified massively in determining efficiency and effective output. Whether based off great pressure from defense or poor execution by the offense, the turnover battle can be indicative of the result of one single game, if not indicative of a larger trend. Additionally, we've seen that to maximize possessions and get higher-percentage shots, teams that move the ball well and have higher assist numbers generally have a greater offensive output. We can see within each system what teams do a great job at this: low team turnover rates or assist numbers are indicative of success. What about on the individual level? Is there a way to quantify a player's "safeness" with the ball for the role that they serve in? Can we examine it across offensive systems without being dependent on teammates or coaching? Probably not, but knowing what to look for when analyzing a player's performance is key. I'll walk you through the process I used to see how strong a player really is with the ball. These numbers are from the 2013-2014 season, as I attempt to remove recency bias, which can be strong when looking at players within their current framework.  TOV% Turnover percentage is a stat that quantifies the turnovers that a player has per 100 possessions. The stat is really only a real indicator for players with a large enough sample size (players on pace for around 1000 minutes played in an entire season). But it goes a long way to showing how responsible they are with the ball and how trusted they can be, particularly in crunch time. Here's a breakdown of stats from last season with the top five at each position with at least 1000 minutes played. The table shows that the players that are more catch-and-shoot players at the shooting guard, small forward and power forward positions are not very turnover prone. The players who handle the ball more at those positions, like Boris Diaw, Andre Iguodala and Lance Stephenson, have higher turnover rates - a byproduct of their playing style, not a surprise. But there are a couple of aberrations, particularly for players who play such meaningful minutes. To see Dirk and LaMarcus Aldridge in the top five is incredibly encouraging; Tobias Harris and Nick Young both handle the ball quite a bit on the perimeter and don't have high turnover rates. The most meaningful data collected here was at the center and point guard positions. At center, we see that Kendrick Perkins turns it over four times more frequently than Al Jefferson despite getting such fewer opportunities to touch the ball. Among point guards, Patty Mills is astoundingly ahead of the pack at 8.2 Point guards have overall higher numbers than all other positions due to the frequency at which they handle the ball. Lillard and Conley, two starters, are on this list despite high usage. Kemba Walker as just outside the top five at 11.6. On the flip side, Ricky Rubio is nearly twice that total with a 21.8 turnover rate. For a player who doesn't shoot a lot, the turnovers likely are to be higher, but this seems really high for a player that just received a four-year extension. It's very telling that the Thunder had three frontcourt players with over a 20% turnover rate: Perkins, Adams and Collison -- hard to argue with Durant and Westbrook's usage rates when their teammates turn it over so frequently. It could also be that the lack of spacing created by so many non-shooters heavily contributes to the turnover rates of unskilled interior players. On the other end of the spectrum was Portland, with three starters in the top five at their position in turnover rate in Lillard, Lopez and Aldridge. It made up for Nicolas Batum's fairly high 18.6 turnover rate (again a product of his usage). The only other team with two starters in the top five at their position was Minnesota with Pekovic and Martin. Turnover statistics, beyond just sheer turnovers and A:TO ratio, are important for frontcourt players as well as guards. But turnovers, by and large, are indicative of playing with the ball in one's hands. An old coaching paradigm is that a turnover is always the passer's fault, and turnover statistics only half-heartedly reflect that. In seeking to balance the TO% numbers with ball-handling metrics, I combined it with ASST% stats, which calculate the percentage of teammates' field goals that the player assisted on. By dividing the turnover percentage per 100 possessions into the percentage of assists, I got this stat: assist to turnover usage ratio. It focuses mainly on those who handle the ball frequently and have high assist numbers. The question seeking to be answered here: do these players create more buckets for their teammates than they cost them by turning the ball over?  This metric seeks to quantify the impact of a ball handler in a "net-positive" sense. The relation between assist and turnover numbers are directly related to the amount of time a player has the ball in his hands. The only way to level the comparisons between players with different usages is to divide the usages together. Chris Paul has long been regarded as the top creator for others in this league, and a stat like this reinforces that. He's a full point and a third ahead of the next-best qualifier, Mike Conley. Only six players are at 2.5 or above, and only Westbrook and Irving had a usage rate above 25% (meaning they took a high volume of their teams shots). John Wall and Stephen Curry, two very different types of players, have a similar impact. The three players here that caught my eye were LeBron James, Kevin Durant and James Harden. Look where the past two MVP's are: 2.22 and 2.19, ahead of Damian Lillard, who was in the bottom of the league's turnover rate. But James Harden is below 2.0, meaning that for every two baskets he assists on, he'll cost his team more than one possession. When I see that, combined with his defensive woes, I note the vast improvements he's made since becoming a primary ball handler in Houston and the effects D'Antoni's system had upon him this past season.  The other factor that needs to be accounted for is the team's system of sharing the ball. Some teams and offensive systems rely on a guard to distribute the ball to others. So I added on a new column to the ASSTrate/TOV% graph with that player's percent of their team's assists per 48 minutes. This table tries to lay the responsibility within each team's system to create assists for others. Some players' numbers will be high if they're the only one expected to create for others. For example, the four lowest on the list are Parker, Chalmers, Lin and Iguodala. Chalmers, Lin and Iguodala have a teammate on this list with a higher percentage, meaning they aren't the main creator on their teams. Parker's numbers are indicative of the extra passing system the Spurs run - assists aren't expected to come just from Parker, they come from the offense. Studying the team's assist trends across their roster in comparison to other teams around the league reinforces that idea. The players highest on this list have the ball in their hands the most on their team: Chris Paul, John Wall and Stephen Curry dominated possessions frequently with the ball in their hands. It speaks both to the coaching system and the lack of other playmakers on their teams at the time, which leads to how that system is built. Some teams may have an incredibly high amount of their assist burden concentrated on two players. For example, Durant and Westbrook combined for 56.8% of their team's assists per 48 minutes last season, meaning that while their turnover rates may be high, the system is designed around them having the ball, so those turnovers are at least coming within the confines of where the usage should be. Curry and Iguodala combined for 54.5%, the next highest teammate tandem on the list. The highest tandem in the league: Phoenix's Eric Bledsoe and Goran Dragic at 59.5%. But the biggest value that the % of team assists statistic shows in this table comes in comparing it with the ASSTrate/TOV% value. When the A:TO rate is high and the % of team assists is low, it means that a player is exceptional at creating for others and maximizing each possession. Tony Parker is the prime candidate here: he assists on 31.7% of buckets while he's on the floor despite not being a prime creator in percentage of the offense, but he takes care of the ball while doing so. Damian Lillard and Mike Conley also fall into this category, mainly because they take care of the ball. Their assist totals aren't as indicative of success because the offense gets assists from elsewhere. Parker doesn't have the flashy stats, nor does Conley, but both excel in accomplishing what they are asked to do. Harmony between ability and role is crucial to success. Conversely, a player with a low A:TO rate and a high % of teams assists gets gaudy numbers in terms of assists because their system relies on them, not because they make tons of great plays. The numbers are driven by two things: high turnover rates (like Ricky Rubio and Kendall Marshall) or domination of the ball within their offense (like Michael Carter-Williams' rookie campaign and James Harden). A player with high outputs in each column is heavily leaned upon in their offense and does pretty well within it. Obviously Chris Paul is the leader here; Kyrie Irving (this is from the days LeBron was in Miami) and Kyle Lowry get high marks here as well. A player with low outputs in both columns means they likely aren't the primary option within their offense as a creator and their turnovers are to the detriment of their team more than their assists are a positive. This includes players like Jeremy Lin and Mario Chalmers. So what the hell does this all mean? It means that we need to look at more than an assist to turnover ratio to see the true value of a point guard. Figure out how much they're being asked to do, both in terms of scoring and creating for others. Then see, based on that usage, how they protect the ball. Hopefully stats like these can serve as indicators as for who does the most good for their team. |

Adam SpinellaHead Boys Basketball Coach, Boys' Latin School (MD). Archives

September 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed